Table of contents

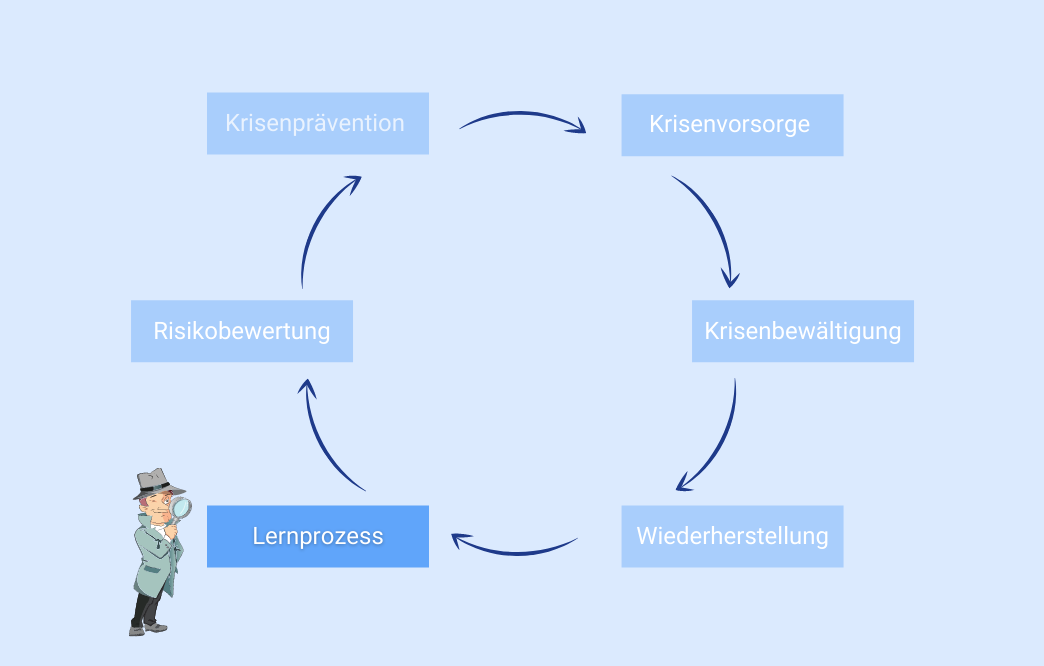

The process of learning is connected in one way or another to all phases of crisis management and therefore plays a role across phases as well as in the retrospective crisis review. In the 8th and final part of our blog series on crisis management, one of the topics is how organisations learn after a crisis and what challenges the learning process brings.

First, we discuss the question of what learning means in the context of crisis management.

Learning process in the context of crisis management

Learning from previous crises is an essential element of risk assessment, which, properly conducted, uses historical data to identify risks and assess their probabilities. But learning from crises also means putting in place preventive and reductive hurdles or controls for risks identified in previous crises. Prevention thus means proactively learning from vulnerabilities based on past experience in order to avoid the crisis.

Learning can also be understood as an important element of crisis prevention. Often, previous crises are used as the basis for training and exercises to equip participants with the necessary skills to put into practice in the event of a crisis. Learning also takes place during crisis management, but learning is complicated by high risks, uncertainty and time pressure. Thus, one is often left with finding good intermediate solutions to problems that cannot be solved by standard procedures.

There is also a learning process in recovery. One should learn from past crises by examining their situational and systemic causes in order to avoid future crises. Although it is not entirely clear exactly where crisis-related learning begins and ends, the learning process is usually seen as a phase following the acute phases of coping and recovery. Failures are explicitly welcome here, because wisdom is only gained through failure, while this is rarely the case with success.

But what are the mechanisms of the learning process? How is learning done? What mistakes are made and how can the crisis management tool GroupAlarm support the process of learning?

Mechanisms, dimensions and levels of learning

Learning from crises differs from general learning in that the former is triggered by a specific event and is not the normal adaptation to changed circumstances or new information. During and after a crisis situation, a more psychological learning process takes place in which circumstances cause actors to change their behaviour and attitudes. This also implies that previously learned behaviours have to be abandoned.

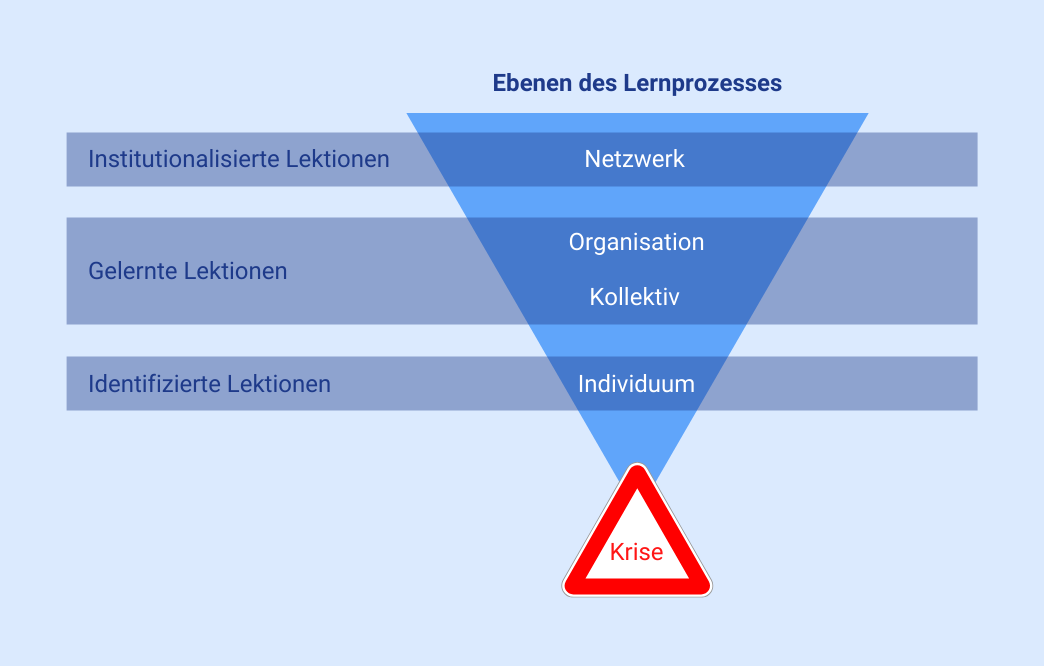

Learning always takes place on several levels. First, individuals learn, which in turn can lead them to initiate a change in the behaviour of the respective organisation. However, this requires individuals who take a conscious and strategic approach to learning from past crises and who are able to drive necessary reforms throughout the organisation. As this individual learning takes place within and for the organisation, it can in some cases be transformed into collective learning processes even before it becomes organisational learning.

This is often referred to as a three-phase learning process with Lessons Identified, Lessons Learned and Lessons Institutionalised. It is argued that the first phase takes place at the individual level and the second already encompasses the organisational level, while an organisation has only truly learned when the change is institutionalised in the organisation’s culture and behavioural practices. In the case of a major societal, man-made crisis, even a whole network of governmental jurisdictions as well as private and non-profit actors may be involved in the learning process (network learning). (See Pursiainen, Christer. The Crisis Management Cycle. Taylor & Francis, 2017. [VitalSource Bookshelf])

Failures in the learning process

In post-crisis learning, a distinction is made between at least two types of failures: First, when one learns nothing from past crises or only things that lead to no change. Secondly, when one learns but draws the wrong conclusions. Many companies put a lot of energy into planning and implementation, but invest very little time in reflecting on what they have done. So they do not approach learning systematically.

But what factors affect whether an organisation learns from the crisis or not?

**Here are a few examples.

- Rigid institutional beliefs enshrined in laws, rules of conduct and customs contribute to mistakes that can lead to renewed crises.

- Tactical opportunism of decision-makers who do not (want to) learn lessons from a major crisis with far-reaching dimensions - e.g. due to board elections.

- Lack of trust in an organisational culture leading to faulty reporting and secrecy or even fear of recrimination or sanctions, which automatically holds back reporting and thus limits the information from which lessons can be learned.

- Incidents with serious consequences (e.g. at critical infrastructures) easily attract media attention and create external pressure that practically forces actors to learn lessons from crises and make appropriate adjustments.

Post-crisis evaluation

After crises, public and private organisations are often required by law to conduct evaluations. The assessment usually takes into account the causes, outcomes, circumstances of a crisis as well as the related phases of crisis management, such as crisis preparation and response. The most important finding is that there is a need for better preparation.

One of the problems with the learning process is that there is no standard for conducting post-crisis assessments. Another problem concerns the subjective nature of the assessment. So, almost by definition, public assessments are not necessarily impartial. Often, they are only about protecting self-interest. Moreover, lessons often remain only lip service, or the findings are not properly communicated to the respective stakeholders due to communication problems.

One way to disseminate lessons learned is through workshops with key stakeholders. Here there is an opportunity to evaluate, for example, the institutional and legal framework, response mechanism, preparedness arrangements, coordination and early warning and awareness raising. Lessons are then learned with the aim of correcting the structural conditions that enabled the failures or at least identifying the bottlenecks in crisis management.

Blame and crisis management

Decision-makers have to explain, defend and often subsequently rationalise their actions in the context of the crisis and commit to change. This process often involves apportioning blame, which is all too often encouraged or even organised by the media.

As a result, polarising fronts such as “heroes” and “villains” not infrequently emerge, at least in external communication. Various aspects such as the nature and sector of the crisis, the timing, the political situation, the interdependencies and the symbolic value of the crisis are just some of the factors that influence the aftermath of the crisis.

Learning process supported by GroupAlarm

As we have already noted in the context of crisis assessment, evaluations are one of the mandatory tasks for companies and organisations when dealing with a crisis. With the help of our crisis management platform GroupAlarm, you can track exactly who did what, when and where after a crisis. All incidents are documented in real time and automatically saved. In the course of this, you receive detailed, audit-proof documentation, reports and log files on all events. These provide you with concrete evidence for your own evaluation within the framework of internal audits, or to prove the actions of those responsible to the authorities in the event of recourse claims, for example.

After the crisis is before the crisis

Learning from a crisis is often a painful process for all involved. There are numerous mechanisms, conditions and reasons that lead to an organisation or company learning or not learning from a crisis experience. The prerequisite is the awareness that learning after a crisis differs significantly from “normal” learning. Instead of blaming each other, the crisis should be used as an opportunity to get to the bottom of the causes and background. And not just to do it better the next time, but to optimise the crisis management process in all phases.